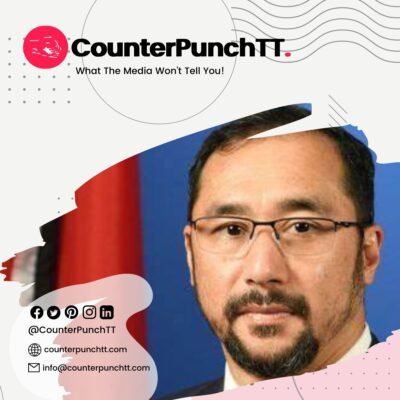

NATIONAL Security Minister Fitzgerald Hinds was guilty of a huge breach of the separation of powers when he instructed Commissioner of Police Gary Griffith not to report for duty.

Confronted with that reality, Hinds backtracked, offering a proviso to his directive to the incumbent commissioner.

But Griffith maintained that, in a telephone conversation, the Minister told him not to return to his job at the end of his vacation.

The issuance of such an order is not within the remit of the National Security Minister or any other government official.

The Police Service Commission has the direct responsibility of managing the commissioner and his deputies.

The Commission is empowered to issue such a directive – with justifiable reason.

The Commission acted belatedly, suspending Griffith several hours after Hinds spoke to him.

Hinds’ order was not only outside of the scope of his legal duties, but was a contravention of the separation of powers principle that dates back to the 1962 national independence constitution.

During constitutional talks at Marlborough House in London, England, the then-political opposition sought stipulated assurances that the government would not tamper with the employment and professional functioning of public officers.

The opposition wanted guarantees that those providing public service would not be politically victimised or favoured.

In hard-fought negotiations, there was agreement on the establishment of independent service commissions to manage public officers, law enforcement workers, teachers, and judicial and legal service employees.

Members of these commissions are appointed by the President of the country, usually for three years, in consultation with the Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition.

Strict stipulations were enshrined to ensure independence and neutrality of all commission members.

The commissions are empowered to appoint, promote, transfer and discipline relevant officers.

Over the years, there have been challenges in the operations of the system, partly as a result of a lack of human and technical resources, especially with the expansion of each sector of employees.

But their jobs are still strictly hands-off to politicians.

Hinds’ instruction to Griffith to stay off his job is a commandeering of the work of the Police Service Commission, whose little-known Chair Bliss Seepersad had been missing in action during the ongoing Griffith imbroglio.

Ms. Seepersad and her fellow commissioners emerged to suspend Griffith after the Hinds intervention.

Throughout the crisis, Seepersad remained voiceless, seemingly ignorant of her crucial constitutional powers and her vital responsibilities the country.

The silence led to speculation about whether the commissioners were being manipulated and were afraid of running afoul of political authorities with an agenda.

Griffith spent most of Saturday huddling with his attorneys, led by Ramesh Lawrence Maharaj S.C.

He has challenged his suspension as being “illegal, irrational and in breach of the rules of natural justice.”

He is threatening a judicial review unless the suspension is withdrawn.

Meanwhile, retired High Court judge Stanley John has told Griffith in a letter that he did not conduct an investigation into the commissioner, nor any other police officer.

John had undertaken an enquiry into an alleged firearm-for-sale racket in the Police Service.

The entire issue is expected to take several twists and turns over the next few days.